Ben Foden, a former England Rugby international player and now a fullback with Rugby United New York, can still remember the first time he played the game. “My dad used to play, and he took me to my first rugby club when I was four,” he says. “Needless to say, I hated it. I didn’t enjoy getting beaten up by all these bigger kids.”

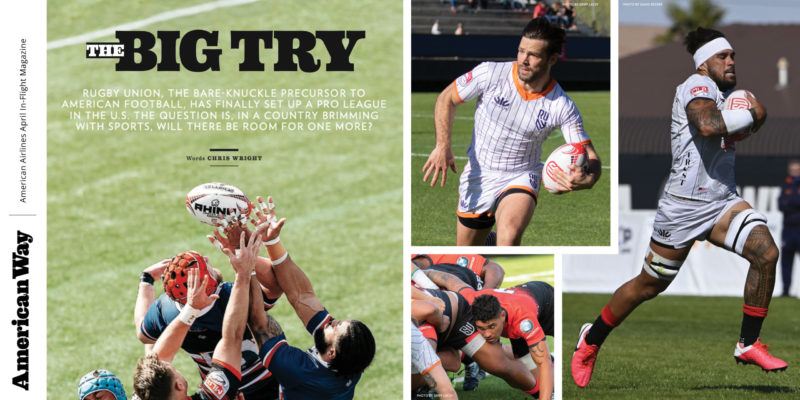

Things are even more combative at the level Foden plays now, as one of the founding players in Major League Rugby (or MLR), which had its inaugural season in 2018, bringing a sport known and loved around the globe for its “elegant violence” to a nation that has plenty of its own sports already. The people behind the league, though, are confident it will flourish, in part because MLR mirrors the end-to-end, hard-hitting speed and grit that has made American football such a popular sport—minus the protective pads and helmets.

“Americans love the fast pace, huge guys running the length of the field, these big hits,” says Foden, who, while enjoying rugby a lot more than he did as a 4-year-old, is still mindful of the toll it takes on the body. “It causes so much wear and tear, and the collisions are getting bigger,” he says. “I count myself very lucky. It’s great to get paid, and get paid well, to run around outside. But it’s also very taxing.”

There are lots of rules to the game, but the aim is to score a try (essentially a touchdown). Think of it as a brutal and continuous option play, with no forward passes and no blocking. Teams also advance the ball by kicking it downfield, and can score points by drop-kicking the ball through the goalposts during live play. Defensively, teams stop opposing players by tackling them and ripping the ball from their arms. All told, the games last 80 minutes.

The combined force exerted on the human body during a game of rugby is said to be on par with being hit by a car traveling at 30 mph. In effect, Psalm Wooching, who plays for San Diego Legion, is that car. “People say I’m pretty violent when I play,” says the six-foot-three back row player, whose position is akin to playing linebacker and fullback in American football—lots of tackling and lots of running. Though he’s thoughtful and gentle in conversation, he also frequently equates rugby with war. “That runs in my blood as a Samoan,” he says with a laugh. “We were built for that.”

Followers of the NFL in particular will appreciate these kinds of sentiments, but MLR is casting a wider net. “Rugby has the physicality of football, the passing of basketball and the grace of ice hockey,” says MLR commissioner George Killebrew. “You’re going to be watching a melting pot of the sports people in America already love.”

Even so, Killebrew knows he has his work cut out for him when it comes to competing with the so-called Big Four (along with Major League Soccer), particularly since the pandemic derailed the 2020 season after just five rounds of games.

Speaking a few weeks before the opening of the new season (on March 20), Killebrew admits to being “a little nervous,” but says he has great hopes for the future. MLR has grown from seven teams in its first season to 12 now, with another team (the Dallas Jackals) set to join next year. Crowds are on the up, sponsorship deals are coming in, and MLR has invested in an OTT streaming service to bring games directly to viewers. “The economic indicators look good,” Killebrew says.

Economic indicators aside, the long-term success of U.S. rugby will be determined by the extent to which it can formulate its own culture, a sense of collective identity and fan loyalty. Already, MLR has shown glimmers of a unique style—with an emphasis on flair and showmanship. It has also attracted a roster of global players with name recognition, talent and charisma. “Our players are some of the most interesting guys I have ever been around,” says Killebrew. “They are exceptional athletes, but they are also colorful and intelligent. Having them makes it more fun. And that’s what people care about.”

Foden, who would not look out of place in a Marvel movie, is one of these colorful characters. He is a tabloid darling back in the U.K.—in part due to his former marriage to Una Healy, a member of the band The Saturdays (along with his, um, spirited vocal stylings on The X Factor). “As a rugby player, you don’t sign up for that,” he says of the clamorous media attention that played a part in his decision to move to the States. “At the same time, doing things like The X Factor, I bring it on myself.”

Foden is also aware, though, that a backstory like his won’t do the league any harm. “Sport needs idols,” he says, going on to identify 27-year-old Wooching as an example of an idol-in-the-making: “He’s good looking, he’s got all these tattoos, he’s always surfing. These are the kinds of people who create the culture.”

Wooching, who was born in Hawaii to Samoan-American parents, played rugby as a teen, and is undeniably interesting. A star football player who captained the University of Washington Huskies, he famously spurned NFL scouts ahead of the 2017 draft, opting to enter U.S. rugby when it didn’t even have a pro league. “I had a great time playing football, and it looked as if I was going to make that next step,” he says. “My last year I had a Cinderella season—we were beating all these great teams, going undefeated, breaking records. The last few games, looking back at that journey, I felt it was time to give up.”

Of course there were people who urged him to reconsider, but he stood firm. “I wanted a new journey,” he says. “My family always told me: Memories and experiences are the things you hold onto in life, not money and fame.”

Right now, Wooching is holed up in an apartment 350 miles northeast of San Diego (health restrictions require Legion to play the 2021 season out of Las Vegas), and he seems a little blue when talk turns to “the beautiful Big Island” where he was raised. “Nothing is going to be as close to home as home,” he says. “You fish during the day, take your catch home and eat it. You drink coffee in the morning in a grass shack and go surfing in the afternoon. It’s the little things that I miss.” (It’s worth noting here that these reflections are delivered by the same guy who describes his role on the field thus: “You see someone coming and go right through them.”)

Winston Churchill described rugby as “a hooligans’ game played by gentlemen.” Certainly, players generally possess levels of civility, humility and camaraderie that you don’t often see in other pro sports. “That’s one of the reasons I love the game,” says Wooching. “Football can get very cliquey and about yourself. With rugby, it’s a battlefield on the pitch, but afterwards you go and have a beer and a laugh. There are no hard feelings.”

This communal spirit is all the more remarkable when you consider the mishmash of individuals who have converged in MLR. “You have international superstars on the same team as a pizza delivery guy,” says Foden. “That’s how crazy it is.”

For influential British YouTuber Robbie Owen (a.k.a. Squidge Rugby), MLR’s mix of nationalities, abilities and personalities has led to a “wonderfully and openly mad” spirit that is starting to attract fans all over the world. “I find myself staying up until 4 a.m. to watch when I really should be asleep,” he says. “It has a cult following, even here. It’s a scrappy underdog that’s punching above its weight, and there is something endearing about that.”

Owen goes on to recall a moment in which the former New Zealand All Blacks Ma’a Nonu, a lionized two-time World Cup winner, was left chasing shadows by a fleet-footed player who describes himself as a part-time juggler. “It’s great to watch someone like Nonu perform,” Owen says, “but it’s a lot of fun seeing someone you’ve never heard of embarrass him. You won’t get that anywhere else.”

Killebrew loves to hear stories like this. He talks about “the beauty of the game,” but he also knows that American sport is about spectacle as much as athleticism. “Right now, we do a pretty good job of getting the faithful to watch,” he says, “but if you want to go beyond the hard-core aficionados, the entertainment value has to be great, too.”

It’s possible that the purists will have a problem with the thrills-and-frills approach that you see in the NFL, but those who actually play the game take a more pragmatic approach. “Cheerleaders, halftime shows and all that—I’m all for it,” says Foden. “That’s what will bring money into the game, which means the game can get bigger. Everyone looks at European or southern hemisphere rugby as the blueprint for how to build leagues. But this is American rugby, and it’ll have that identity stamped on it.”